Shadowrun for Sega Genesis: Please Tip Your Proxy Warriors

John Ferrari, Contributing Editor

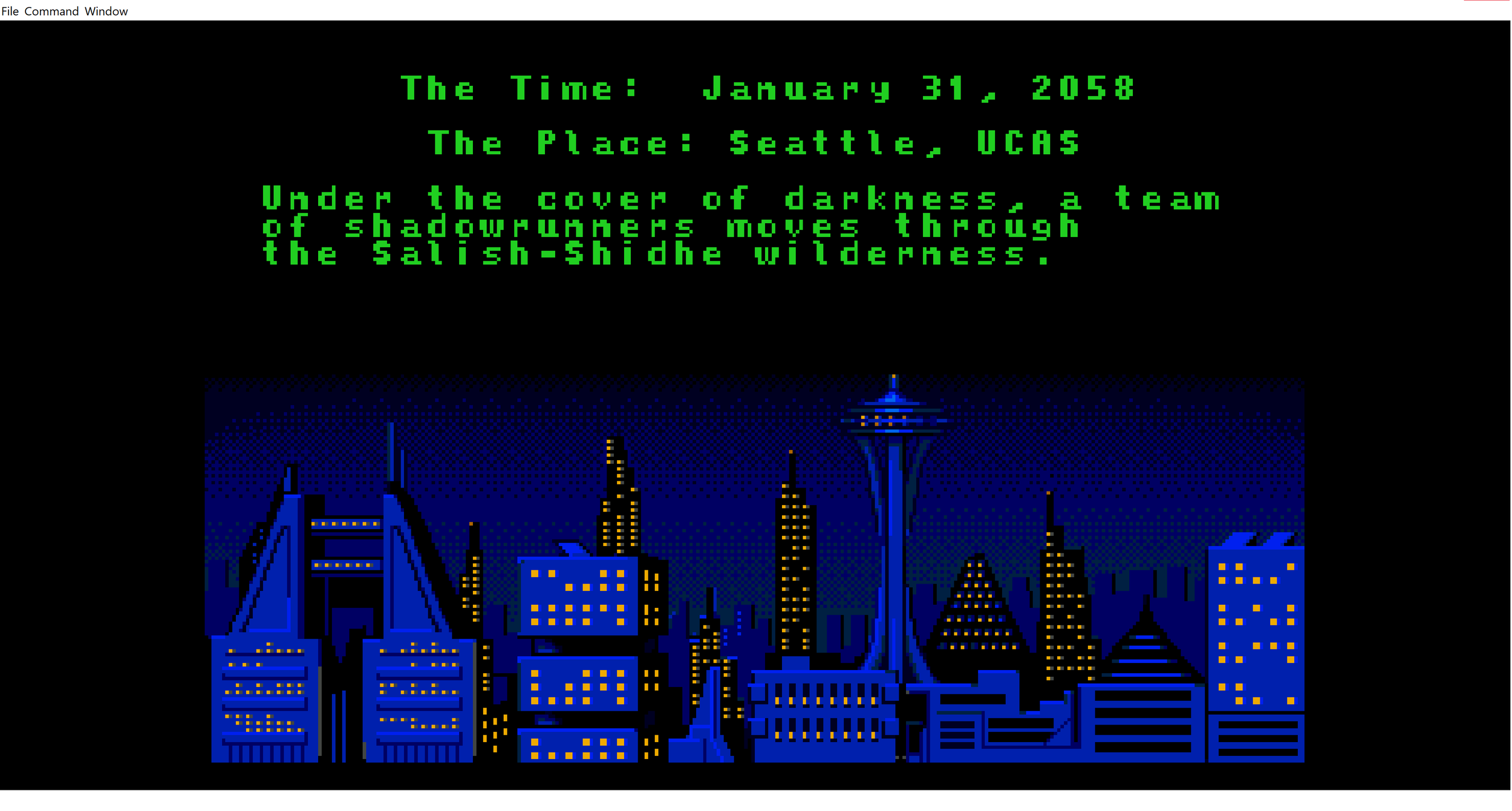

In the summer of 1994, developer Bluesky Software released the cyberpunk roleplaying game Shadowrun for the Sega Genesis (Mega Drive). The player takes control of “Joshua” who travels to Seattle in the year 2058 to investigate the death of his brother. While the game was reasonably well reviewed, fate dealt the developers a tough hand. Similar to its cyberpunk subject matter, Shadowrun for the Genesis was a cerebral sci-fi dystopia born into the fringes of a media landscape that placed little cultural value on genre fiction. Both the arcade and home console market at the time were dominated by the unstoppable trifecta of Mortal Kombat 2, Super Street Fighter 2, and NBA JAM Tournament Edition. However, despite the game’s debut into general obscurity, Shadowrun stands as one of the best examples of cyberpunk on any gaming platform and arguably the most openly political game on the Sega Genesis.

Shadowrun is an outlier in the cyberpunk genre in that it includes many high fantasy tropes as a core element of its game world. The Seattle of 2050 is one populated by Orcs, Elves, and dragons. Corporations have wizards on salary and your roommate may moonlight as a shaman for hire. Including magic as a core element of the game world is a firm declaration that the narrative is not an exercise in simple speculation or prediction. Similar to a fairy tale, the game is engaged in constructing a contorted reflection of the world as it is, rather than a peek into future possibilities. Importantly, the world the game describes is one in which private profit has supplanted public good as the primary governing principle.

The term “shadowrun” is defined in the fiction of the game as a task that’s been subcontracted to a “shadowrunner” (mercenary) by a corporate entity through the use of a third-party intermediary known as a “Mr. Johnson.” It’s a system designed in a way that allows for corporations to have covert violence committed on their behalf while maintaining protective anonymity. Shadowrunners are badass cyborg samurais and street savvy combat mages. Importantly, though, the ranks of shadowrunners you encounter are drawn exclusively from the economically disenfranchised. College drop-outs, former convicts, and the wrongfully terminated, among others, are forced to endure violence and personal risk to fend for themselves in a system devoid of a social safety net.

While many games in the 16-bit Sega era require the player to amass currency, few games (if any) linger so much on poverty. The player finds themselves at the start of the game so lacking in funds that they are unable even to retrieve their dead brother’s personal effects. Players quickly discover currency is king and that all interactions are transactional by default. In Shadowrun, society has fully embraced neoliberalism as the primary governing principle. Whatever services and protections were once offered by the government have long since been privatized by the time the player enters the scene. Repeatedly throughout the course of the game, the player is reminded that healthcare, safety, and infrastructure are luxury items available only to those who can afford them.

By 1994, the crusade against the social safety net was already well underway in the United States. The Reagan administration (now, playing a starring role in Call of Duty: Cold War) had aggressively lobbied to reframe welfare as a fraud-ridden “poverty trap” to American voters. Presented as “reforms,” a series of proposals such as work-fare sought to shrink the number of welfare enrollees. Relatedly, the dissolution of the Soviet Union was held up as evidence of the wisdom of market capitalism victorious over a failing communist system. Business lobbyists and politicians began the neoliberal push for privatization across all levels of government, while the world order attempted to fill the power vacuum the Soviet Union left in its wake. The apotheosis of the free market had begun in earnest.

In Shadowrun, that power vacuum is filled by corporate interests. By 2050, many aspects of public life like law enforcement have fully transitioned to private business. The justice system, for instance, is handled by the for-profit Lone Star Corporation. As a result, law enforcement has become even more unevenly distributed and transactional in nature. The Seattle of the game is divided into 5 distinct districts. Of those districts, 3 feature heavy corporate and commercial presence. These districts feature offices, night life, and high-end shops. Most importantly, they feature heavily armed patrols by Lone Star. The 2 remaining districts both carry the label “barrens” and are home to primarily industrial and abandoned buildings. Like many near future dystopian works of fiction, the slums of Shadowrun are a mixture of Dickensian industrial squalor, Hollywood ultra-violence, and racist fears regarding urban minorities communities. Criminal infractions are met with either deadly force or resolved through bribes.

Within the game, it’s obvious that law enforcement exists to protect the wealthy and keep violence contained to the impoverished districts of the game. Policing and justice had become national issues in the years directly preceding the release of Shadowrun. 1992 had seen wide scale protests and rioting in response to the acquittal of the L.A.P.D officers who brutally assaulted Rodney King. The anger and violence that erupted in the streets were brought directly into homes by a rapidly evolving media landscape. Emerging media outlets like 24-hour cable news and primetime tabloid news found easy content and eager viewers when covering crime for their programs. Events like the L.A. Riots and the Willie Horton Case made it so that being “tough on crime” was a bipartisan boon for any politician seriously seeking public office. For many communities in 1994, the justice system in Shadowrun was only marginally different from the one they engaged with daily – a state of affairs that has only intensified for many low income and communities of color in the intervening years.

It’s important to point out that shadowrunning is by and large not a peaceful enterprise. Corporations in the game aren’t content to fight their battles in court or have the invisible hand of the market decide their bottom line. The boardrooms of Seattle demand results and bloodshed is the cost of doing business. To satiate shareholder greed, corporations enlist the aid of economically-disenfranchised individuals, risking death for a chance at a better life. Crucially, while shadowrunners work “on behalf” of corporate benefactors, they don’t “work for” those corporations. By filtering all recruitment through “Mr. Johnsons,” business secures an insulating layer of protection from the legal ramifications of armed violence. It’s a system that both creates and exploits economic precarity. Absent a durable social safety net, the only measure of social mobility available demands that those who seek an escape from poverty endure and commit acts of violence.

The connection between capitalist endeavors and armed conflicts has been present from the inception of publicly-traded companies. Both the Dutch and British East India companies made frequent use of armed proxies in their efforts to secure the spice trade. From the late 19th century into the early 20th, American fruit corporations in cooperation with the U.S. military waged aggressive campaigns of subjugation in Central America and the Caribbean. These conflicts coined the term “Banana Republics” to describe countries that resisted corporate control and as a result saw their governments upended by the U.S. military. The conflicts were so explicitly commercial in nature that US Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler was inspired to write “War is a Racket” in response to the war profiteering he personally witnessed during the U.S. occupation of Haiti. Game developers didn’t need to look far for inspiration.

Mechanically, most of Shadowrun’s in-game systems are a simplified version of the original tabletop RPG. To make progress, players take on missions, the proceeds of which allow them to purchase information regarding their brother’s death. As players complete missions they’re rewarded with “Karma Points,” which can be used to upgrade the player-character’s stats. Fitting for a game so focused on neoliberal talking points, the only resource the player should ever be concerned with is Nuyen (pronounced New Yen), the in-game currency. Nuyen enables the player to procure all manner of weapons, armor, and hardware. Combat takes place in real time and can be brutally quick. Thankfully, the game lets you hire other shadowrunners for your party. True to the game’s ethos, your party members are not just disposable but easily exploitable. Some of the savvier strategies for the game involve hiring shadowrunners only to strip their gear for resale.

A 16-bit Sega game might not seem the most obvious place to find a political narrative that speaks to the present. In an era known more for its candy-colored cartoon mascots, there was little real incentive to craft a layered tale of corruption and corporate malfeasance. Yet Shadowrun for the Genesis found the time and cartridge space to not only create a unique and fun murder mystery but also an indictment of corporate greed and violence. To date, Shadowrun for Sega hasn’t seen any rerelease or remaster but cheap copies can be found on eBay. It’s easy to understand why Shadowrun faded so quickly from memory. It was a game born to be forgotten, an outlier in every category it finds itself in. But no other game so fully embodied the punk ethos like Shadowrun. In an era dominated by games claiming to have “attitude” or be “edgy,” Shadowrun is one of the only games that manages to deliver an anti-authoritarian sneer.

For more critical takes on cyberpunk, check out Christian Haines’s guide to the genre, “Technical and Crude,” and Don Everhart’s essay on surveillance and prisons in Deus Ex: A Criminal Past.