Why Mother Brain Terrifies Me

Roger Whitson, Managing Editor

Metroid was the very first game I owned as a kid. Its brand of sci-fi horror contrasted sharply with the cartoony enemies of Super Mario Brothers and even The Legend of Zelda. I became particularly squeamish over the dragons in Norfair who popped their heads out of lava and spewed fire in an arc that I couldn’t dodge. The metroids were frightening: jellyfish with red nuclei and sharp teeth. Yet, few of the horrors of the original game matched the experience of encountering Mother Brain for the first time. A pink lumpy blob of flesh with wires emerging out of her skin, throbbing, and encased in glass — I wondered where the brain came from. Did it once belong to a giant who had died long ago?

Image courtesy of Metroid Wiki.

Mother Brain is surrounded by zebetite, described on the Metroid wiki as “regenerative ore-like material,” yet to me they looked like fleshy spinal columns, tentacles housed in metal tubes, or extensions of the same lumpy mass making up Mother Brain’s body. The zebetites, turrets, and flying rings of energy called rinka conspire with the tricky slowdown of the final room to give the ending of the game a feeling akin to a nightmare. Meanwhile Mother Brain lacked a face, making her largely a blank, inscrutable terror.

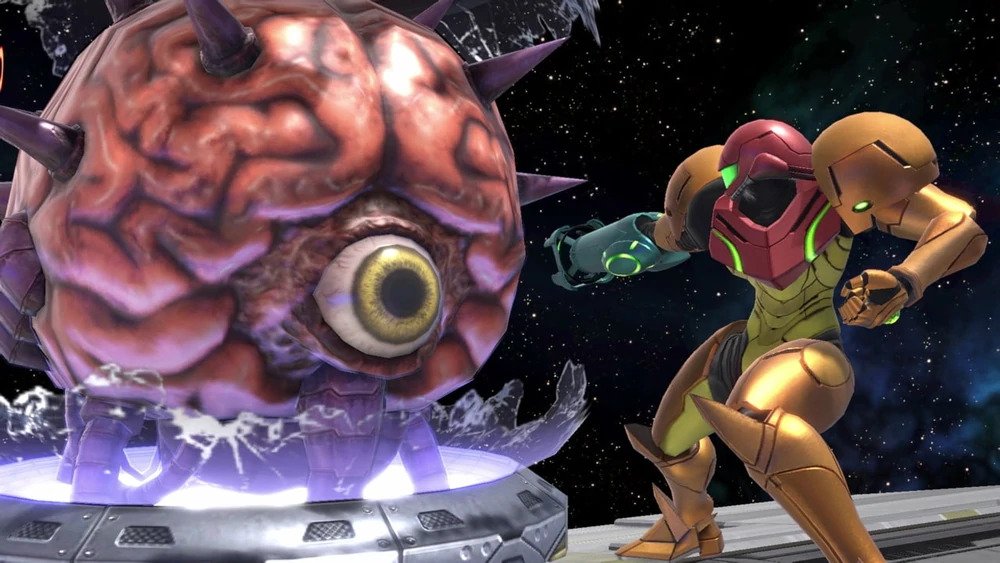

Mother Brain lost much of that inscrutability when developers added a blinking eye, a mouth, a repurposed body in Super Metroid (1994) — and she’s retained those features ever since. To be completely fair, the Mother Brain who appears after Super Metroid is much more menacing than the one depicted in the NBC cartoon Captain N: The Gamemaster (1989-1991). Captain N features a teenager named Kevin Keene who — with the help of Mega Man, Simon Belmont, Kid Icarus, and Gameboy — battles Mother Brain and her minions King Hippo and Eggplant Wizard. Mother Brain was voiced by Levi Stubbs, who sang for The Four Tops and played Audrey II (a predatory alien plant) in the 1982 film version of The Little Shop of Horrors. Stubbs transferred Audrey’s boisterousness and vanity into his depiction of Mother Brain, lending a tone that became more comedic than horrific as the series wore on.

Image courtesy of Metroid Wiki.

What is it about a disembodied brain that’s so frightening? To me, Mother Brain was all the more terrifying for having such a blank expression. Was this simply because she seemed completely indifferent to my efforts as Samus? Or was there a deeper, more existential aspect of terror that manifested when I saw that lumpy mass appear?

The trope of the disembodied brain is common in science fiction and horror. One of the best-known examples is H.P. Lovecraft’s novella The Whisperer in Darkness. Lovecraft is, of course, known for using horror and disgust to vent his quite repugnant racist views. The Whisperer in Darkness is no different. Lovecraft’s story centers on a literature professor Albert Wilmarth who is investigating the stories of Henry Akeley. Akeley says he has evidence of extraterrestrial creatures who are able to extract a human brain, place it in a canister, and launch it into space. As the narrator Albert Wilmarth describes hearing it from Akeley: “[t]he bare, compact cerebral matter was then immersed in an occasionally replenished fluid within an ether-tight cylinder of a metal mined in Yuggoth, certain electrodes reaching through and connecting at will with elaborate instruments capable of duplicating the three vital faculties of sight, hearing and speech.” The novella ends with Wilmarth convinced that he’s seen Akeley’s discarded face and hands and heard bizarre voices coming from a cylinder housing Akeley’s disembodied brain.

Image courtesy of Metroid Wiki.

Wilmarth’s description sounds precisely like the original design for Metroid’s Mother Brain: compact cerebral matter, occasionally-replenished fluid, electrodes reaching through and connecting at will. In The Whisperer in Darkness, the horror of the disembodied brain is tied tightly to the way we process experience. What does human experience mean when a brain is disembodied and its senses mediated by electrodes? What about our own sense that what we experience has a reference to an outside world? Can a brain in a cylinder have ethics? Love?

Subsequent lore in the Metroid series, in particular the manga that appeared in tandem with the release of Metroid: Zero Mission in 2004, reveals Mother Brain to be an artificial intelligence created by the Chozo in order to watch over the planet Zebes. Corrupted by the Space Pirates, Mother Brain decides to extend her program of control and surveillance throughout the galaxy by conquering it. The first issue of the Metroid manga depicts Mother Brain’s arrogance when carrying out her primary functions, so her corruption and betrayal are not surprises.

Image courtesy of Metroid Wiki.

Metroid’s lore describing Mother Brain as an artificial intelligence ultimately detracts from the uncanny terror I felt when venturing into the final room of Metroid for the first time. Such fears are connected to my own anxieties involving embodiment. Could it be that I’m just a brain in a cylinder experiencing a simulated reality? Metroid: Dread features a call-out to Mother Brain in the form of Central Units. These are blue-colored brain-shaped mini-bosses surrounded by canons and rinkas that serve to control the EMMIs in the game. The placement, number, and size of the Central Units in the game, as well as their pretty banal-sounding name, make them poor substitutes for the brain-in-the-box terror of the original Mother Brain. Staring into that inscrutable, fleshy mass without a face, I’m forced to confront the limits of my body and agency. Mother Brain terrified me because, unlike Audrey II or the various versions of the character appearing after the original Metroid, it left me with only silence as the answer to one of the oldest existential questions: what am I without a body?

For more Metroid musings, listen to the Episode 1 of Retronomicon, where we discuss the Metroid series, and read Christian Haines on Samus’s morph ball ability.