Mourning, Melancholy, Edith Finch, and My Mother

Christian Haines, Managing Editor

What Remains of Edith Finch (Giant Sparrow, 2017) was released about a year after my mother unexpectedly passed away. I played it a few months after its release, in the fall. I knew little about the game, except that it was a walking simulator – a genre with which I had only passing familiarity. My interest in it had to do with the novelty of its gameplay. I didn’t know that the game would send me into tears, that I would find myself reexperiencing the scene of my mother’s passing in an endless loop. If I had known more about its story, I probably would have avoided the game.

* * *

What Remains of Edith Finch asks players to endure death after death as they explore the history of a family and its ancestral home. In most games, death is a pitfall structuring a challenge; it goads the player to improve their skills. Even in narrative-driven games, death is functional. It’s a recipe for emotional investment, a way of introducing dramatic stakes into a story: kill off a character early in the narrative in order to highlight the dangers that surround the game’s protagonist (see Last of Us Part 2, for instance). Edith Finch is different. Death doesn’t punctuate the plot, it is the plot. The game isn’t dramatic in the classical sense. There’s no obvious rising and falling action. Instead, it’s a melancholy cycle, moving through loss in a way that emphasizes the passage of time but without the promise of anything like progress. Usually classified as a so-called walking simulator, Edith Finch is probably better understood as a death simulator.

* * *

What dramatic arc Edith Finch possesses is undercut by its incessant repetition of death. The game multiplies death into a series of episodes. Its overarching structure is simple, even formulaic: the player tours a house and its immediate surroundings; each room or locale contains an object – a journal, a set of photographs, a comic book – gesturing towards something specific about the Finch family member who inhabited the space; the object serves as a portal into a vignette about the death of that Finch, with bespoke gameplay mechanics highlighting the distinctive personality of the deceased. The game spatializes the history of a family, translating architecture and interior design into opportunities to replay events of death.

One of the reasons I’ve avoided replaying this game is because some of the deaths in the game are difficult to play through. There’s one in particular that makes me shudder: you play as a baby in a bathtub; your parents argue in the background; the tub drains only to refill because of your own actions; and you drown. As in most of the episodes, tonal dissonance reigns. The game presents the tragedy as a fantastic scene in which the child’s toys come to life, the bathtub water becomes a beautiful ocean, and drowning is a dive into serene depths – all set to the cheerful melodies of Tchaikovsky’s “Waltz of the Flowers.” Another episode frames the murder of teenage starlet Barbara Finch as a campy horror comic narrated by a humorous cryptkeeper. Instead of approaching death with high seriousness, Giant Sparrow uses irony in the form of a contrast in tones that overturns the player’s somber expectations. This makes the experience of death ordinary. Although the game emphasizes storytelling, or the way in which our lives get memorialized as stories passed down from one generation of a family to another, the stories it tells aren’t epic. They’re quirky, strange, sometimes even absurd, but they are always profoundly ordinary. They’re tales of family grief. Nothing more or less.

* * *

Since my mother’s passing, I tended to avoid stories in which death played a prominent part. I didn’t mind the gore of a first-person shooter or the spectacular destruction of an action film, but I screened myself off from anything that confronted death as a meaningful event. I had constructed a set of barriers dividing the present from the past, ensuring that my memories of my mother were less visceral, less tactile, more like glimpsing the flickering light of a neighbor’s television from across the street. It’s not as if I had no direct experience with death. I had lost grandparents to cancer, a cousin to AIDS, another grandparent to Alzheimer’s. My mother was the caretaker in the family, so these deaths weren’t distant things – they were intimate affairs that I witnessed unfold across weeks, months, years.

* * *

What Remains of Edith Finch isn’t a walking simulator or a death simulator, then. Maybe it’s a mourning and melancholy simulator. The distinction between the two, at least for Freud, was that the latter is a failed version of the former: melancholy is what happens when you can’t get over the loss of a loved one, so you find substitutes onto which you can transfer and reenact your feelings. You’re stuck in the past – the moment of loss – even as you’re not really capable of acknowledging what’s gone missing from your life.

Edith Finch, the titular protagonist, seems to mourn just fine. In fact, she’s a thin character, more a cipher of family legacy than a well-developed personality. The house and the family, on the other hand, they strike me as melancholy figures, weighed down by their past, turned inward so that they’re constantly reliving their history of misfortune. You see this melancholy in the elaborate gravestones in the family cemetery, as well as in the way that the rooms of the deceased are sealed off, as if to preserve the past in a kind of stasis. You also see it in the game’s general atmosphere of foreboding, the sense of inevitable doom that has as much to do with its individual episodes as its linear progression.

The critical and fan favorite episode featuring Lewis Finch exemplifies this foreboding. What’s so compelling in it is the imaginary kingdom of Lewistopia that Lewis dreams up while working at a cannery. This kingdom resembles a bright fairy tale world, filled with princes and princesses, ornate castles and a dreamy river. However, the episode’s momentum is determined by the cannery’s conveyor belt, which hums ceaselessly along, delivering one fish after another for canning. With one thumbstick on your controller, you move Lewis through the wonderland of his imagination; with the other, you perform his job, slicing fish in preparation for some distant grocery store shelf. The player can only move their controller’s thumbsticks in a rhythmic pattern until they eventually deliver Lewis to his death on the factory floor. There is no escape. You can only go deeper into the twists and turns of the Finch family history.

* * *

My mother died suddenly, unexpectedly, from breast cancer that had spread to her lungs. It had gone undiagnosed until it was too late. She checked into the hospital thinking she had bronchitis. A few days later she went home with cancer. She died less than 48 hours later. I remember her screams of pain when we brought her home, before the hospice caretaker could administer morphine. For a long time, I found it difficult to separate my memories of my mother from these screams. It was as if death were an overzealous editor who had rewritten her life with a red marker.

* * *

I called Edith a cipher, more a window into family history than a proper character. But that’s not quite true. What defines Edith for the player is her will to knowledge, as well as the fact that she’s pregnant, bearing the next member of the Finch family line. In other words, the game’s player-character combines a will to know with the narrative seeds of the future, so that in a paradoxical fashion, digging into the remains of the Finches – into the house’s secret corridors, the family’s whispered losses – becomes a project of recovery: if you endure all of the game’s episodes, it gifts you with the tentative hope of a child who just might be able to carve his own path through life, one not so determined by the curse of family history. Not unlike therapy, Edith Finch takes the player from melancholy to mourning by reckoning with the past.

* * *

Edith Finch didn’t erase the pain of losing my mother, but it did bring me to a place where I could begin the journey from melancholy to mourning. It invited me to experience death in its ordinariness. It used irony to dedramatize loss, to reintegrate it into the rhythms of everyday life. Irony can be cruel. It can dismiss pain. But irony can also remind us of the contingency of our feelings, the way even the most serious matters offer themselves up to humor. In the hours following my mother’s death, before her body had been taken away by the funeral home, my father, my sister, and I told morbid jokes, while reminiscing about my mother’s life: Donna Marie Bruno Haines was strong and stubborn, quick to anger, filled with laughter, charming and moody, intelligent and caring. She was a pagan priestess, author of a book on witchcraft and community-building (Witch in the Neighborhood). She took charge of arranging Christmas festivities when my grandmother passed, and she once surprised my sister and me with a trip to Disney World. She was always surrounded by stacks of books, as if the sheer accumulation of words might serve as protection from the evils of the world.

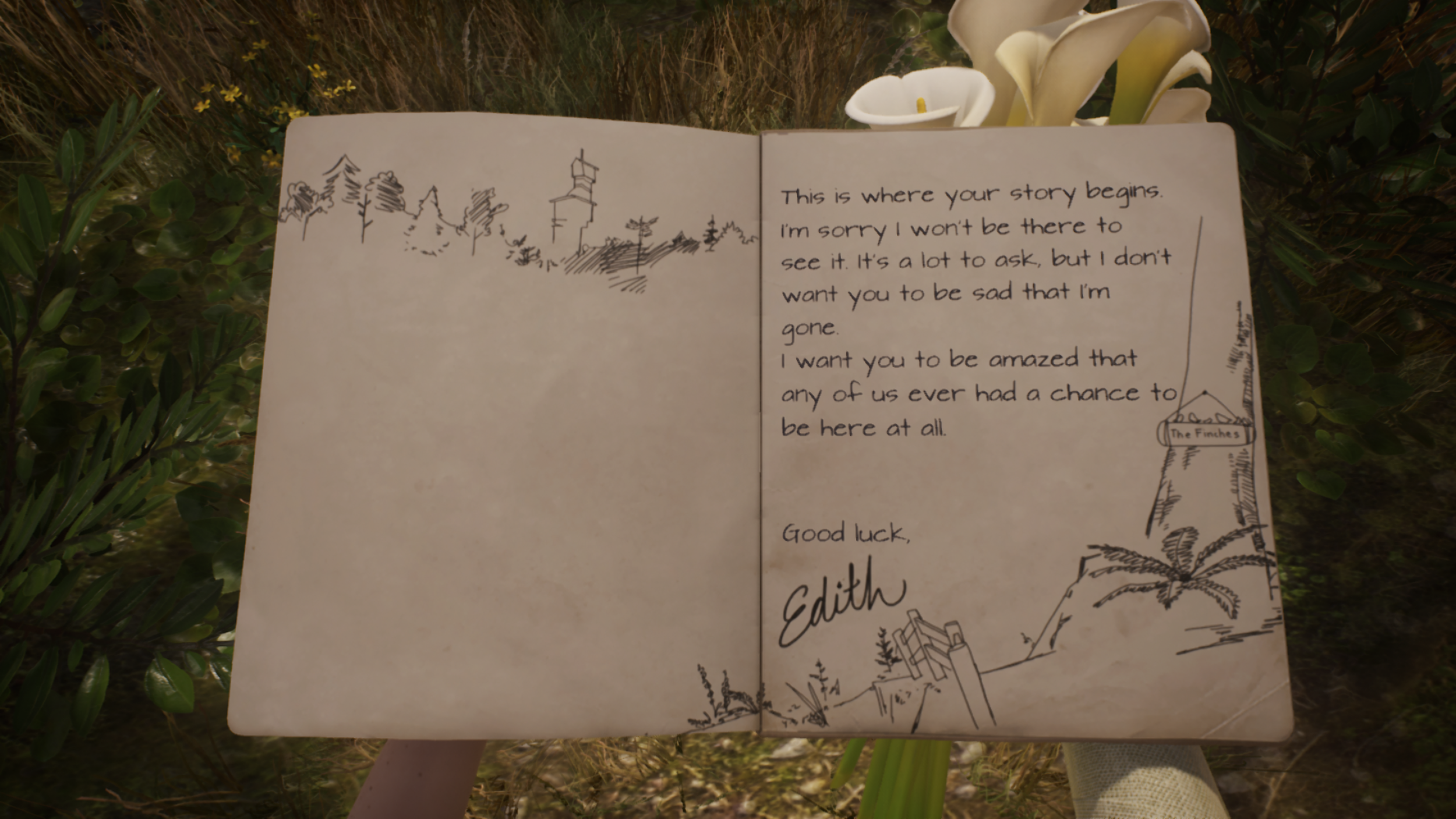

We’ve experienced a great deal of loss and hardship in our family, but my mother always insisted that we find joy even during the longest nights, the shortest days. For her, the winter solstice wasn’t the darkest day of the year, it was a turning point, the moment when the death and decay of winter began to prepare the way for spring’s rebirth. Giant Sparrow’s game ends with Edith’s son laying flowers at her grave, reading the last words in her journal: “This is where your story begins. I’m sorry I won’t be there to see it. It’s a lot to ask, but I don’t want you to be sad that I’m gone. I want you to be amazed that any of us ever had a chance to be here at all. Good luck.” I won’t pretend my mother’s pained screams have disappeared from my memory, but when I hear them, now, I don’t turn away. Instead, I think back to her laugh, to the way she opened my eyes to all the wonders of living.

For more in our “Shortest Day, Longest Night” series, read Don Everhart on Pathologic 2 and Jason Mical on the power of Kind Words in a struggle for mental health.