Mourning my cats with Stray

Roger Whitson, Managing Editor

“The partners do not precede the meeting; species of all kinds, living and not, are consequent on a [...] dance of encounters.”

—Donna Haraway, When Species Meet

For Buddha, Nemo, Templeton, Boo, and Opus.

Spoiler Warnings for Stray

CW: cat euthanasia, mourning, and death

1. After a cutscene in Stray where your robot companion B-12 overloads his system fighting off a horde of Lovecraftian enemies, you gently nudge him awake. “It was dark,” B-12 says. “I was alone. It felt like I was back in the network. But you saved me. Thank you, friend.” B-12’s brief existential reflection is quickly complicated in the upcoming stage by an empty body, which is revealed to be B-12’s former human self. The scene underscores the mourning at the heart of the game. B-12 is a ghost in the machine, a human consciousness that had forgotten he had ever been human. Stray is not just about playing a cat, it also depicts the last moments prior to human extinction. Their ghosts and traces are everywhere.

Stray dropped a few weeks after Buddha died. I dreaded playing the game, but I also knew I couldn’t ignore it. My kitty Buddha was the subject of a previous article on Gamers with Glasses, where I mentioned how he was my only companion during the dark nights of the first pandemic winter in 2020. I said he was fine then, and he was. In June 2022 Buddha abruptly stopped eating. I remember pacing around the courtyard in front of my apartment, waiting for the vet to tell me what time I could drop him off. Nothing was found in his labs, but a small abnormality appeared on his ultrasound that signaled either irritable bowel disorder (IBD) or lymphoma. The next step was exploratory intestinal surgery to confirm a diagnosis, then chemotherapy. It seemed much too much for my boy. The vet clinic was so noisy. Dogs barking, multiple owners standing in line. They had a process to drop off your pet in the early morning, to cut down on the line and allow the doctors to examine animals during a break. But it also meant that Buddha spent hours in a carrier, sick, unaware of when or if he’d see me again.

Buddha being cute a few months before his illness (2022).

2. Stray introduces your unnamed cat-character while they play with the other members of their clowder. (Yes, groups of cats are called “clowders,” and a group of kittens is a “kindle”!) Your character is an Orange Tabby based upon three separate cats in the lives of Koola and Viv, BlueTwelve’s cofounders: Murtaugh, “known as ‘The Boss’ by those who love him” inspires the cat’s orange coat; Oscar, a hairless Sphinx, acted as the physical model for the cat’s fluid movements, as well as inspiring the cat’s curiosity and agility; and Jun, a Black Shorthair “was in charge of monitoring the team’s efforts every day and making sure everyone was working on the right topic.” A brief sequence begins the game in which you variously play, sleep, and groom one another — then are separated from them. The scene is gut wrenching. The other cats climb, jump, and run across rusted pipes, broken concrete walls, and precarious balance beams making up Stray’s post-industrial wasteland. After attempting to jump a gap between two rickety pipes, one of them breaks and you plummet into a wall. The game cuts to a close-up shot of your cat’s anguished and sorrowful face as you anxiously claw onto the concrete and desperately attempt to find a purchase. But you eventually fall into the abyss below. The entirety of the game revolves around your quest to reunite with your clowder. But they are never seen again.

Separation from the Clowder in Stray.

3. Philosopher Donna Haraway is a dog lover and calls cats companion species “in extremis,” but I’ll cut her some slack (Reconfiguring 301). Companion species include humans and their various pets, dogs and cats but also birds, lizards, horses, and other domesticated animals. She questions the notion of “unconditional love” often projected upon pets by their owners. In turn, she says, we treat our pets like children. She finds the habit pernicious and abusive, setting pets up for “the risk of abandonment when human affection wanes, when people’s convenience takes precedence, or when the dog fails to deliver on the fantasy of unconditional love” (Manifesto 38). So-called “unconditional love” replicates the condescension we show children in the nuclear family onto our pets. Yet Haraway also shows that our connection to pets is much more profound than many think. She speaks lovingly about how companion species become entangled with one another, calm one another, leave traces in one another’s lives. We didn’t just domesticate or invent pets, we co-evolved with them. They invented us as well.

I met Buddha in a PetsMart in Atlanta, GA. He was partially named after my childhood pet Boo, whose death I recounted in my previous article, and partly because of Buddha’s limitless love and compassion. Everyone he met was instantly his friend. Buddha purred, rotated his head in a manner that I’ve never seen in any other cat, and — as they say in Georgia — “made biscuits” with his paws. I tried picking him up, but quickly learned he didn’t like that. His back claws hadn’t been trimmed in a while, and he slashed open my chin. I only got permission to take him home from my partner “on a trial manner.” Of course, that would be the only time Buddha drew blood from me. He was almost preternaturally gentle, accidentally a feline embodiment of his name. A week after Buddha arrived, we learned that our other cat Templeton was suffering from FIP (feline infectious peritonitis). FIP is a common coronavirus in cats that usually manifests as a common cold. However, in a small percentage of cats the virus mutates and, afterwards, has an almost 100% fatality rate. Over the course of the next month, we saw Templeton deteriorate. Buddha wanted to play, like many kittens, but we had to keep him in a separate room because Templeton was too sick. The night Templeton died, we rushed him to an emergency vet while Buddha was crying in another room. I sang softly to Templeton in the car as he kept gasping shallow breaths and his tongue hung limply out of his mouth. He was only five months old. I suspect much of Buddha’s caring nature came out of that trauma. He only knew Templeton for a brief moment. But he could sense our sorrow and gently cuddled with me as I slept. In those moments, Buddha invented me.

Buddha’s first picture, with Templeton on the right (2009).

4. One of the favorite pastimes of redditors when interacting with Stray is posting pictures of their cats watching them play. “She even tried to sniff the player cat’s butt,” says Tortie_Shell; while teslaCal exclaims, “I love it so much when she plays with me.” And others, like vindemiatryx98, are inspired by the game to rescue real cats: “‘Owning a tabby cat would be awesome,’ I thought while playing Stray and this guy showed up at my door, in a cardboard box, along with his little sister.” I’m under no illusion that a video game can solve the problem of pet overpopulation at overcrowded shelters, where approximately 530,000 cats are euthanized each year, but it’s heartening to see some of them at least temporarily adopted. Further, Annapurna Interactive hosted livestreams of the game on Twitch to raise money for animal shelters.

A significant subset of the posts includes tributes to cats who died before their humans started playing the game or while they were in the middle of their playthroughs. “RIP to my old cat smokey, says PICONEdeJIM. “She loved sleeping and scratching furniture.” In addition to the regular responses to such posts, “[s]he had a happy life,” players also wonder if they can continue with the game. “My cat was so fascinated,” Casinate remembers, “RIP Spaghetti.” Spaghetti “died from a cobra bite a few weeks ago, don’t know if I’ll be able to play the game for a while.” I didn’t know if I would be able to play the game either, though it also felt like a way to connect temporarily with my departed kitties. I struggled for weeks figuring out if I could craft a proper tribute to Buddha while also reflecting on the nature of loss and companionship. While many games have focused on the loss of friends and family, playing Stray to process Buddha’s death felt incomplete, filled with gaps, and ultimately unsatisfactory. But when doesn’t mourning feel this way?

5. The first cat I euthanized was Opus, named after the Bloom County character. He and I had a close bond. He would sit on my lap, legs sprawled out, like some caricature of an old manspreader. Opus had kidney failure. After months of peeing blood and dialysis, my mother decided to let him go. I was so angry with her, not only for making what I thought was a premature decision, but for also not accompanying us to the vet office. It was only when I had to make the decision to euthanize Buddha years later that I could empathize with my mother’s sense of uncertainty in the face of such a decision — and what must have been a very deep loss. Opus crouched in my lap until he was injected with the drug and collapsed into nothingness. Immediately after leaving the office where Opus was euthanized, my body was so distraught. A friend of my stepmother Charrie was at the office and waved at her. I don’t remember consciously making any choice, but I instinctively ran and hugged this stranger. I didn’t know her at all and never saw her again. As I drove back to my graduate school in St. Louis, I remember the snow falling on my front window, listening to Nico’s cover of Jackson Browne’s “These Days” on repeat, and endlessly sobbing. Of course Nico’s song has nothing to do with cats, but her melancholic voice combined with the plucking guitar made me remember my Opus bounding across a room with his tail high in the air.

Opus manspreads as he sits on my Lap (2001).

4. The final stage of Stray in the “Control Room” depicts B-12’s sacrifice to help you get to the Outside. That we experience what is technically a moment of extinction as a sacrificial gesture of connection exemplifies the game’s critique of the narcissistic fears found in many representations of human extinction and apocalypse. We are more connected than we realize, the final human seems to be saying as a copy of his consciousness flickers out of existence. “I’m sorry we won’t see the outside together.” he continues, “I thought I needed to carry on the memories of humanity. To hold onto the past. But, I see a future in the Companions. And you.” Companions are the group of robots originally created to be the friends of humans in the underground layers of Walled City 99. Like many of the cats and dogs in our world today, the Companions are simply left to fend for themselves after humanity disappears. The robotic bodies and gestures of the Companions remind me of Ray Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains,” in which an automated smarthouse is the only survivor after a nuclear holocaust. The house runs through its automated processes with no humans present, with various animals in the yard as the only observers. Then, a stray flame from a cigar lit by the house catches fire and burns the house down. The Sara Teasdale poem which inspired Bradbury’s tale is also quoted in the story:

Not one would mind, neither bird nor tree,

If mankind perished utterly;

And Spring herself, when she woke at dawn

Would scarcely know that we are gone.

B-12’s final soliloquy in Stray challenges Bradbury’s narcissistic loneliness. Both robots and animals are companions in Haraway’s sense of the term: “they more than change each other; they co-constitute each other” (Reconfiguring 307). Stray’s companions demonstrate a deeper and more substantial connection than the soulless automatisms and mute animalities found in the blank observers of “There Will Come Soft Rains.” The thought of a city, completely devoid of human beings, run entirely by animals and robots seems dystopian. Yet instead of recoiling from the horror of these visions of isolation and extinction, B-12 finds only companions. “You were my friend, the very best I could have asked for. Thank you.” He shudders and collapses lifelessly on the floor. You headbutt him a few times and lay near him before moving on.

Your cat mourning B-12 after his sacrifice in Stray.

The cat in Stray looks more like my Orange Bengal Nemo than Buddha, who was a Black Shorthair. Nemo was Buddha’s companion for years. They spent all of their time together. When Nemo became nervous, and he frequently annoyed us with his anxious crying and spraying, Buddha would sit in front of his carrier as if he was protecting him. When I broke up with my partner of 12 years in 2018, she took Nemo while I kept Buddha. “Because you’re his person,” she said. As I left for a vacation so my ex-partner could gather her things, I suspected that Nemo would be gone when I returned. I took several pictures in case I never saw him again. And indeed, my suspicions were true. I arrived home, and he was just gone. A few years later, as I sat with Buddha and the vet delivered those dreaded words — “there’s little else we can do” — I wondered if Nemo still remembered the endless, numbered days he spent with Buddha. The few weeks prior to my appointment were filled with my anxious attempts to deny the reality of Buddha’s illness. Perhaps he only had irritable bowel syndrome, or maybe I could give him chemo for a couple of years. But I experienced a horrible and beatific moment of acceptance when Buddha started vomiting. Much like he comforted me when Templeton died or when Nemo left, I suspected that Buddha was teaching me a lesson: that part of love is letting go.

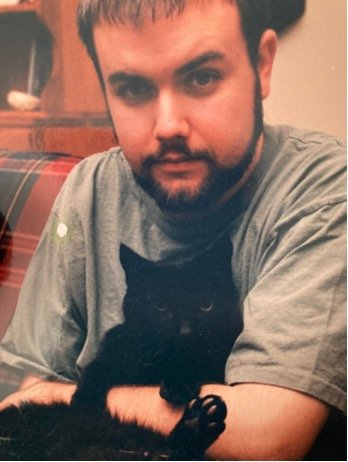

My last picture with Nemo (2018).

In the vet’s office, my girlfriend Cassandra cradled me and Buddha as I put my arm around him and stroked the soft fur on his belly. He loved belly scratches. The vet injected the drug and he relaxed and shrunk up and that was it. He was just gone.

Buddha: you were my companion, the very best I could ask for. Your love inspired me. Thank you. <3

Buddha’s ashes on my Dresser (2022).

Donna Haraway, “Cyborgs to Companion Species: Reconfiguring Kinship in Technoscience.” The Haraway Reader. London: Routledge, 2004, 295-320.

Donna Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago, U of Chicago Press, 2003.

For more on Stray, check out Claire Brownstone on animal protagonists and Christian Haines on what it’s like to be a cat.