Animal Well and the Realistic Surrealism of Childhood

Nate Schmidt, Managing Editor

According to the ubiquitous anecdote, Shigeru Miyamoto was inspired to create The Legend of Zelda by his time spent playing outside as a child. To be completely honest with you, I get the comparison, but the first Zelda game doesn’t actually remind me all that much of playing outside. The items that Zelda gives you to work with are the stuff of fire and fantasy, magical tools that your youthful imagination might have been able to conjure out of a stick or a tennis racket. If you want a game that encourages sends you off exploring with the actual tools of childhood, you’re going to need to play Animal Well.

Nostalgia often paints childhood with rosy glasses, as if our earliest years were some blissful Neverland where, even if everything wasn’t perfect, we at least didn’t have the same problems that we have as adults. Bills, rent, insurance—depending on the privileges afforded you by your social class, these things may have felt like incomprehensible matters that dwelled in the murky future of adulthood. Carefree images of bounding through the forest and digging under rocks, if you get them at all, only paint half a picture. Childhood is terrifying. You are small, mostly helpless, and without defenses. You feel like a little blob in a world that mostly ignores you. As Mo Willems, the children’s book author and creator of the infamous Pigeon Who Must Not Drive the Bus puts it, “Probably the most fundamental insight is that even a good childhood is difficult: You’re powerless; the furniture is not made to your size.”

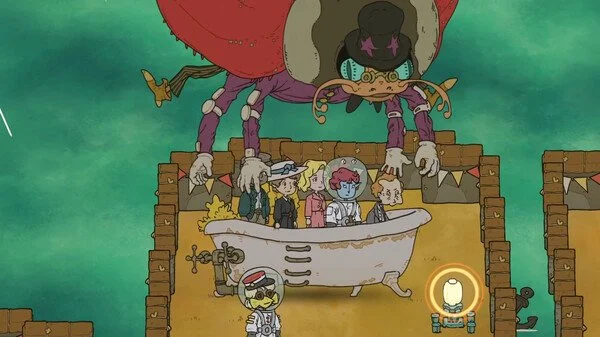

It’s dangerous to go alone. Screenshot by the author.

That’s what it feels like to play Animal Well. You’re a powerless little blob armed with a slinky, a yoyo, and a frisbee. You can try to stave off the attacks of nightmare creatures with fireworks. Some animals are safe to interact with, and some are not. You wander around a little bit aimlessly at first, but like a kid who envelops themselves in a fantasy narrative that they craft as they traverse the neighborhood, you slowly make meaning for yourself out of the puzzles that you encounter as you go. The game is a little bit like Metroid in that some things do get easier once you find the various items scattered throughout the world, but I also understand people who say that the comparison isn’t really apt, for all the trappings of the “metroidvania” that are present here: Animal Well is a little microcosm of surrealistic fantasy all its own, in which the rules are not always laid out for you ahead of time and wandering is its own reward.

I can straightforwardly tell you that some of these puzzles are hard as hell, and sometimes I got annoyed with them; there should also be more save points. If there are truly mind-bending quantum level puzzles within puzzles à la Tunic in this game, as some people say, I have not yet been clever enough to find them. Nevertheless, Animal Well lets me relive the experience of exploring a world that is equal parts melancholy, inscrutable, and rewarding, and it consistently invites me to use my limited tools in creative ways. This game feels so familiar, but I’ve never seen anything like it before—like a false memory, or a dream.