Morality Is Shadow of the Erdtree's Big New Feature

Nate Schmidt, Managing Editor

Let’s leave the question of difficulty aside for the moment. It’s hard; we agree.

Instead, let’s talk about quests. Shadow of the Erdtree has quests! Not some random jar in a hole that you might stumble into and might not, depending on how much you wander around. Not a weird little guy who is literally disguised as a tree among trees. Not a shrimp salesperson in the middle of a lake infested with giant crustaceans. In Shadow of the Erdtree, there are people standing next to checkpoints who give you maps that tell you where to go. I’ll say it: Elden Ring is Skyrim now, and I’m happy about it. All I ever wanted was someone I could help, and I have a whole crew of mighty misfits just waiting for me to ride off with them into the Shadow Realm. None of them have quite stolen my heart like Siegmeyer of Catarina from the first Dark Souls yet, but Moore the salesperson is getting pretty close. (Where did he get his stuff? He found it! He likes finding things! Do you like finding things?)

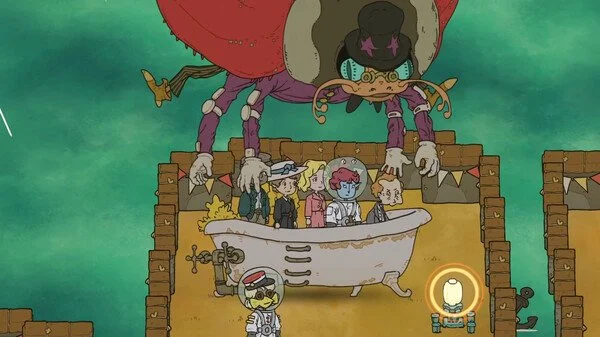

“Finding things” is the whole point of Elden Ring; screenshot by the author.

I have not yet gotten to the end of the DLC—if you can believe that—so it is possible that I am about to make some assertions that will be proved inaccurate with time. But it is currently my overarching impression that Shadow of the Erdtree marks a shift in the wind of moral neutrality that sweeps so powerfully over the base game, by creating a situation in which any action, including the destruction of all parties, has a moral valence to it. At regular Elden Ring’s Roundtable Hold, Gideon Ofnir breezily responds to one of the most despicable acts of another NPC with the fact that morality is irrelevant to the task of becoming the Elden Lord: “The Roundtable has no code to speak of.”

In typical FromSoft fashion, Elden Ring sets itself beyond good and evil, narratively speaking. You can align yourself with the Noble Goldmask or the “loathsome Dung Eater”; either way will set you on the path to Lord-dom. Maybe you trust the Golden Order fundamentalists, or maybe you would like to burn the whole world in the fires of chaos. Reasonable people could disagree, but I would argue that all of the game’s available endings create a pretty crappy situation for at least some, if not all, of the inhabitants of the Lands Between. Nevertheless, if you don’t like the ending you got this time around, you can just play through again and get a different one.

Shadow of the Erdtree doesn’t exactly break with this tradition in a straightforward or jarring way—certainly, not with anything that came with as much of a shock as the straightforward, easy-to-follow maps of Miquella’s Crosses. Item descriptions in the new DLC often reference a “crusade” or a “holy war” being carried out by the followers of Messmer the Impaler against the hornsent or “the tower folk.” Needle Knight Leda, the NPC who originally invites you into the Realm of Shadow, later shares some background information that seems at first to reflect the both-sidesism that you’d expect out of a FromSoft story: “Long ago, Queen Marika commanded Sir Messmer to purge the tower folk. A cleansing by fire. It’s no wonder [nearby NPC] the hornsent holds the Erdtree in contempt. That aside, man is by nature a creature of conquest. And in this regard, the tower folk are no different. They were never saints. They just happened to be on the losing side of a war. But it’s still a wretched shame.”

A little on the judgy side, if you ask me; image by the author.

If it wasn’t obvious enough from the fact that they call him “the Impaler,” this conversation clearly marks Messmer as the agressor. The Realm of Shadow is littered with giant poles on from which mangled bodies dangle in threes or fours, and some of them are on fire. Messmer was doing what his god told him to do, but he clearly did it with the inquisitorial zealotry of a true fundamentalist. It even seems that Queen Marika might have known that she had found the most violent and despicable person for the job. At this point in the quest, I just have to take Leda’s word for it that the tower folk were never saints; some of them do seem to be out to kill me, but so is everyone else, and one of them got really excited when I showed her my cool new hat. However, this conversation marks a significant moment, because Leda makes two uncharacteristically firm pronouncements: people are “creatures of conquest,” and it really would be better if things weren’t that way.

For me, this statement encapsulates the moral conflict at the heart of Elden Ring. So many video games are ultimately about conquest, from Galaga to Crusader Kings 3 to [the cartoonishly un-self-aware] Call of Duty franchise. In her sweeping and (we certainly hope) inaccurate judgment of human nature writ large, Leda nevertheless acknowledges that Elden Ring belongs on this list of games that, however ambivalently, play like conquest simulators. Get bigger, get buffer, so you can slay your biggest, buffest enemies. And yet, for all the talk about how the difficulty of FromSoft games makes victory feel more meaningful, I think we need to also consider the possibility that these fights are so difficult because killing these characters isn’t supposed to feel good. No matter how many levels I put into my faith stat—and I have quite a few by now—I can’t ever play Elden Ring as a saint. If I don’t kill all these enemies on both sides of this conflict, there’s no game. But, as Shadow of the Erdtree asks more slyly than any other title from this developer so far, isn’t that kind of a wretched shame?

I would really like to say that Shadow of the Erdtree is FromSoft’s sneaky acknowledgment of how brutal you have to be in order to beat these games. You have to be willing to spend multiple hours of your actual mortal life trying to kill a single made-up person. I want the developers to be saying, “We put you in this tricky situation, using the charged language of ‘holy war’ and ‘crusade,’ because we wanted to show you that we knew exactly what we were doing when we told you to go out and conquer this world.” I can’t honestly say, though, that I have absolute confidence in this interpretation. For every little moral judgment that gives me pause, there’s an even cooler implement of destruction waiting for me at the end of the boss fight. If you are going to give me a pair of swords that can blast my enemy with pretty blue sparks and roast them with a raging fiery inferno, you bet I’m going to burn a Somber Ancient Dragon Smithing Stone on those puppies. Double the swords; double the carnage. Time, and the rest of the DLC, will tell me if I’m playing or being played.