Interview with Adam Vian, creative director of Crow Country

Earlier this year, SFB games released Crow Country. It’s a survival horror puzzle box set in a theme park that holds some dark secrets past, present, and future. Previously on Gamers with Glasses, contributor Dylan Atknison wrote a review that considered how Crow Country is situated within the subgenre of survival horror. Dylan applauded the story, and, in particular, how its scale transcends the immediate setting of the park and lives of its characters.

With Crow Country’s release on new platforms (including Nintendo Switch and PS5), I had the opportunity to ask a few questions to Adam Vian, the creative director of the game. I asked about how the game emerged, Vian’s thoughts on horror and how to make a game scary, and, at the end, one really specific question about the game’s characters and ending. If you don’t want to know about that last part, stop reading at the image of Mara and “2106”. If it were me… I’d be curious. And I know there are those of you out there who have also played the game and are curious, too.

Don Everhart, GwG: The first questions are ones that I think you've heard a few times. With Crow Country, SFB has hopped genres and styles again. What's your motivation for hopping from genre to genre and style to style? What do you think has carried over to Crow Country from their previous work in Tangle Tower and Snipperclips?

Adam Vian, SFB: Sometimes when you spend a lot of time on a project, you find yourself wanting to work on something completely different. It's been nice to be able to go between those three genres (2D physics puzzle game, 2D detective adventure game, 3D survival horror game) to keep things interesting for ourselves. I did spend a long time trying to prototype the follow-up to Snipperclips, and there were a few candidates, but in the end Crow Country was the project that took hold.

I think the throughline between all of our games would be puzzle design. Snipperclips, Tangle Tower and Crow Country are all puzzle games, basically. It's a skill that I'm always honing, and it applies to whatever genre of game you might be making. The pillars of good puzzle design - communicating with the player through visuals, leading them to think a certain way, making sure they're not being distracted or misled - they're universal.

Don: Next, a question about the setting. Theme parks are touchstones of game design, and there are a few famous theme parks in horror games. What was SFB's inspiration in setting the story of Crow Country in a theme park?

Adam: It just seemed like it would be a fun setting. I realised early on that a theme park would give me great variety - you could have various themed 'lands', utilities like gift shops and bathrooms, and staff-only areas like corridors and offices. It was very easy to fill out the map with interesting and appropriate areas. I was aware that Silent Hill has touched on theme parks a couple of times, but it didn't feel like something that was particularly overdone - not quite yet.

I've always been fascinated with the areas of theme parks you're not supposed to see - whether it's behind the animatronics in a boat ride, or a control room lined with monitors. I've always wanted to be able to freely explore those forbidden spaces by myself, so building Crow Country was a kind of personal wish fulfilment.

Don: Related to that, a question about the story. While it becomes clear that the theme park is cover for Crow's more insidious and greedy operation, which came first: the setting, or the plot?

Adam: The setting came first - before I had any kind of story, I'd settled on a theme park. It wasn't 'Crow Country' at the start, but I knew I wanted it to be a theme park that was a good deal smaller and cheaper than Disneyland. After that, the next thing to solve was the question of why there would be monsters. Really, that issue is at the core of most horror games. Where have the monsters come from? What kind of monsters are they, and why? Is it supernatural/paranormal, or is it science-based? Once I'd landed on a idea I liked for that, the rest of the story was built around it.

Don: Tying back to the first question, did you plan to make a horror game at the outset? Or did that come into place after developing other elements of the setting and plot?

Adam: Yeah, I set out to make a survival horror game. That's really all I knew going in - I just wanted to try it out, since I'd come to realise that it's my favourite genre. I wanted to make something that captured that special timeless magic seen in the first few Resident Evils and Silent Hills. But I had no skills making 3D games, action games, or horror games. So at first, I tried to keep things very small and simple. The first page in my notebook says 'Make the smallest possible survival horror game'. I didn't know it was going to grow into a full-size thing, that just happened as I kept working on it.

Don: Big picture question: what makes a game scary?

Adam: In my opinion, there are three things you could be scared of while you're playing a game:

1. Anticipating something making you, the player, jump - this is a pretty visceral sensation because being made to jump is a physical reaction, almost like pain.

2. Anticipating seeing something horrible, unpleasant or disturbing on the screen. Usually this would be the visual appearance of the enemies, but it can be anything.

3. Anticipating your character being hurt, and possibly dying, therefore undoing progress you've made in the game.

The best and scariest horror games combine all three of these in a graceful way so you don't even consider them to be separate things. And with all three, it's really about the anticipation - rather than the actual instance of them happening. When the enemy actually does appear, it can even be a relief.

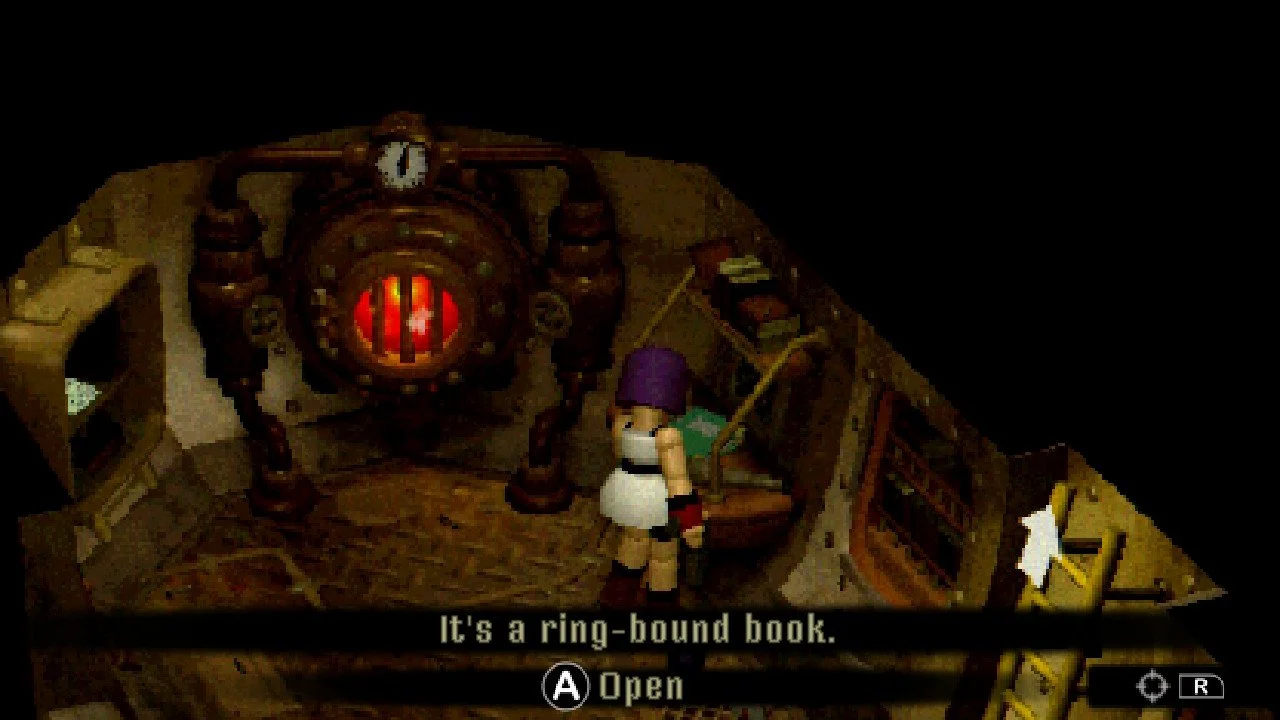

Mara Forest, in purple hair and white dress, stands in a backroom of Crow Country. She faces the numbers “2106”, which appear to have been sloppily scrawled in blood on a wall. A crate large enough to hold an adult human occupies the side of the frame, with an open grate inset to its side.

Don: And finally, a question about the theme. It seems to me that the theme of the game is, to put it simply, that actions have consequences. For Crow, this is thoroughly depicted by the events of the game and the ending. But it applies to Mara a little more subtly, too, in how she steals Officer Harrison's ID, slashes his tires, and then continuously tries to put him off of the investigation and out of the park. In the end, he dies a somewhat meaningless death, still in the dark about the mysteries of Crow Country, and a lot of that is Mara's fault. Do you consider Harrison to be as integral to this theme as I did? What about the other secondary characters?

Adam: It's funny, I actually added Harrison to the game fairly late in development - but I'm very glad I did, as he's probably my favourite character. And yeah, I'd agree Mara is somewhat to blame for his death. Ultimately though, he was just too pure and naive to survive the desperate, dangerous world of Crow Country. I think Harrison's death would probably have affected Mara more if she didn't believe she was heading directly to her own demise.

I'm not quite sure about the theme of 'actions have consequences' and how it might relate to the other characters beyond Crow. Tolman, for example, was partially responsible for the Root Excavation, but he leaves the park with the others at the end - although we don't know what happens to him after that. I think it's likely that the law catches up with him, or else he lives a life of misery because of what he's been part of. With all the characters that make it out at the end, Mara included, their fate is supposed to be an unanswered question. After all, the real theme of the game as I see it is summed up in the sentence that Mara utters at every save point, and one last time before the credits roll.

I got in touch with Adam via Rachel Macpherson at Neonhive, who also provided review codes for Crow Country. As usual for GwG, PR played no part in the questions or publication of this interview.